More than a fancy word, use it to improve results in swim lessons

By Jo An M. Zimmermann and Stacey Bender

Aquaticity is a term historically used in biology and refers to the capacity of an organism to function or be comfortable in an aquatic environment (Vaveri et al., 2016). By focusing on skills such as breath-hold capacity, buoyancy, propulsion, and physical conditioning (endurance and strength), participants can develop a higher level of comfort in the water (aquaticity improves). The idea is the higher a person’s level of aquaticity, the more comfortable and secure the feeling is in an aquatic environment.

© Can Stock Photo / goldenKB

Why consider using aquaticity? The six skills recommended for testing can be used with any swim-lesson program at any swim level ages 5 and above. As drowning statistics increase, there is a need to provide quality swim lessons with an emphasis on safety.

What did we do?

During the summer of 2022, a research study analyzed efficacy using aquaticity skills to measure improvement in swim lessons. A total of 81 students were enrolled in three locations in central Texas, from June to August 2022. Students were given the option of participating in the study.

Thirty-six students completed the pre-test, while 33 completed both the pre- and post-test for an overall participation rate of 41 percent. Participants included 19 females and 14 males. Ages ranged from 4 to 15 years. Participants were 38.5 percent Hispanic, Latinx, or of Spanish origin, 35.8 percent Caucasian/White, 12.8 percent identified other/not listed, 7.7 percent African American/Black, and 5.1 percent American Indian or Alaskan Native (see Figure 1).

The ratio of swim instructor to students ranged from 1:1 in private lessons to 6:1 in group lessons. In most cases, evaluators conducted the pre-tests before any instruction, and completed the post-test before, during, or after class on the last day.

Participants were asked to demonstrate their competency in six aquatic skills, each one scored on a scale from 0 (does not perform) to 5 (successfully performs the task with advanced complexity) points. An overall aquaticity score is calculated by adding the six swim-skill scores together. The highest overall score a single participant can achieve is 30 points. The six skills include the following:

1. Floating: Maintaining a supine (face-up) float position for 15 seconds

2. Bobbing: Exhaling inside the water rhythmically 10 times

3. Gliding: Performing an underwater glide with a push start from the wall of the pool, maintaining a hydrodynamic position

4. Freestyle: Demonstrating a freestyle swimming technique for 25 yards (breathing every three strokes)

5. Treading water: Keeping one’s head out of the water, while maintaining a continuous vertical position:

a) for 15 seconds with both hands in the water

b) for 10 seconds with one hand raised outside the water

c) for 5 seconds with both hands raised outside the water

6. Three-minute fitness swim: Swimming continuously using any style.

Skills-testing sheets (copyrighted and available for sharing with agencies in their programs) were created for use with both individuals and groups.

What did we find?

Analysis of the combined results from swim lessons across the three communities demonstrates an increase in skill level in all six tasks (see Table 1). Overall, there is a moderate increase of 2.77 points or 8.3 percent in aquaticity swim skills. Figure 2 illustrates the results.

As shown in Figure 2, the most significant improvements were in floating, treading water, and freestyle swim skills, but improvements were also made in bobbing, gliding, and 3-minute swim. Thirteen of 33 children were beginners, with improvement indicating that swim instructors concentrated not only on introductory-level skills, but also on higher-level skills.

Table 2 illustrates the differences from pre- to post-test by gender. Female students began with a higher score than males in floating, bobbing, and the 3-minute fitness swim. Male students ended with higher scores in all skills except the 3-minute fitness swim. Overall, males improved 3.54 points vs. females, who improved 2.21 points.

Table 3 indicates that students at all start levels improved in aquaticity skill level. Those who began at lower levels improved more, but also had more to learn. Beginners improved in all skills; however, nine students attempted skills during the post-test that they were originally unwilling to attempt in the pre-test. Participation in the post-test skills indicates increased confidence in themselves and the swim instructors. Advanced beginner and intermediate swimmers saw the most improvement in freestyle swimming, while advanced swimmers improved the most at treading water. Although there were slight improvements in three of the four levels, it appears not much effort was put into fitness swimming (swimming for a specified length of time), as all scores remained low. One aspect that seems clear is aquaticity-skills testing does appear to discriminate based on the level of the swimmer. The scores for intermediate and advanced swimmers were close at both the pre- and post-test, which concludes there is not much difference in skill level between the two groups.

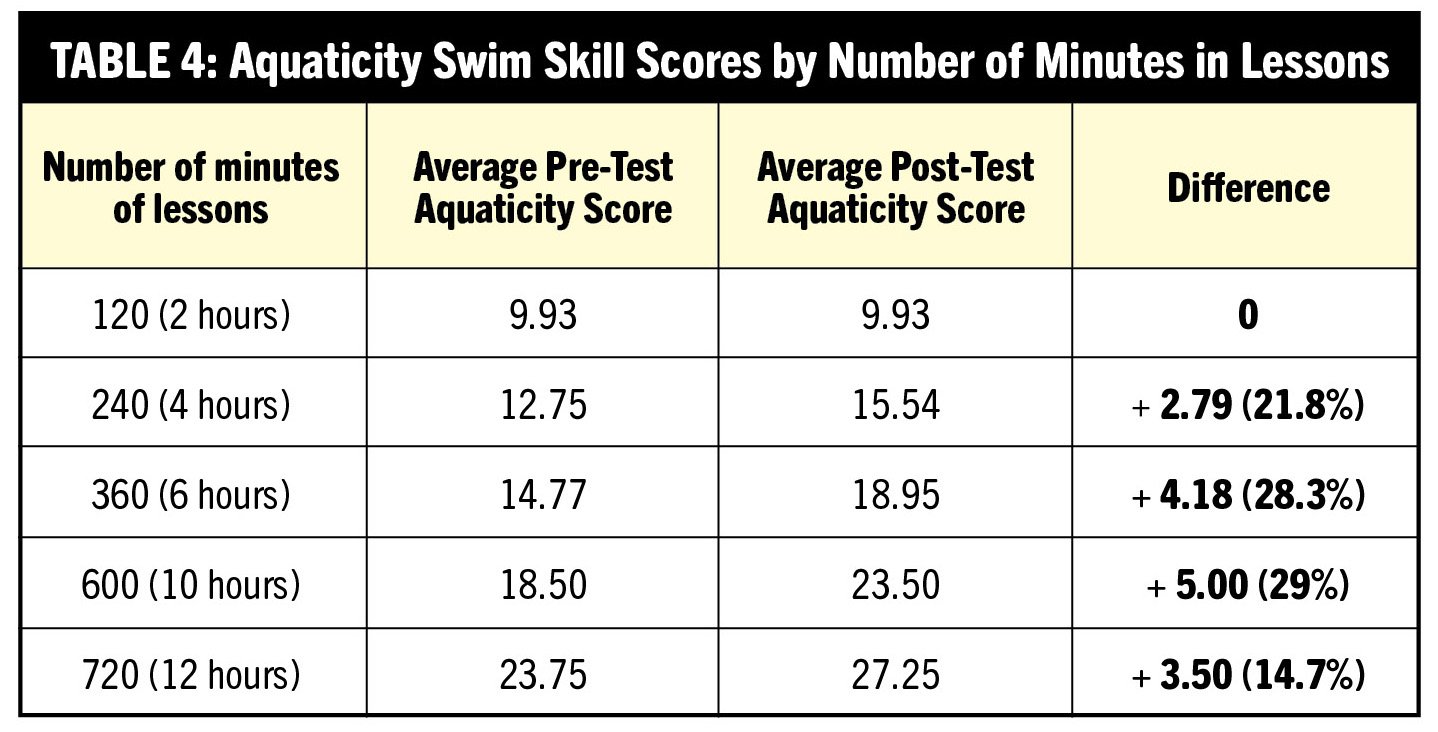

Table 4 illustrates the total amount of time in minutes of classes compared to the overall average improvement, calculated by the average difference in pre-to post-test aquaticity scores. The highest increase in score, 5 points, was by participants who completed 600 minutes (10 hours) of swim instruction. Participants who completed the least class time, 120 minutes, saw no change in aquaticity scores from pre- to post-test.

Finally, swimmers who requested lessons vs. those who were signed up by their parents both showed improved aquaticity (Table 5). Those who requested the lessons started and ended at a higher skill level than those whose parents made the choice for them, suggesting that once a student experiences some success in lessons, they choose to continue.

How Can This Information Be Used?

There are four ways aquaticity skills can be used to improve programs:

1. Assessing learning ability in swim skills. The skills being tested have been identified as helpful in reducing drowning; regardless of the swim program, participants above the age of 5 should be working on these skills. Children under age 5 may not have the motor development to work on all of them.

2. Grouping swimmers. By far the biggest issue with any skill-based class is putting participants into the correct level. Use the six skills as a pre-test on the first day of lessons. Then use the aquaticity score to group swimmers by ability level. Participants can sign up for lessons with no level indicated. If enough staff members can teach 24 students, for example, open 24 spots and assign them to an instructor on the second day of class.

3. Evaluating staff members. If staff members are required to teach these skills and students with a particular instructor are not improving in one or more skills, perhaps more in-depth training is necessary, either in what should be taught or in how to teach the skills.

4. Using the information to make necessary changes in aquatic offerings. Lesson packages can be expanded/changed if participants are not excelling at the expected pace.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the World Leisure Organization as part of its Strategic Priorities Grant Program. Thanks to the cities of Kerrville, New Braunfels, and San Marcos, Texas, for allowing us to work with their swim programs. We hope the knowledge gained will be used to improve swimming programs in the future.

References

Bloomberg Philanthropies. (n.d.). Preventing Drowning. https://www.bloomberg.org/public- health/preventing-drowning/#overview

Denny, S. A., Quan, L., Gilchrest, J., McCallin, T., Shenoi, R., Yusuf, S., Hoffman, B., Weiss, J., & COUNCIL ON INJURY, VIOLENCE, AND POISON PREVENTION. (2019). Prevention of drowning. Pediatrics, 143(5), e20190850.

Denny, S. A., Quan, L., Gilchrest, J., McCallin, T., Shenoi, R., Yusuf, S., Hoffman, B., Weiss, J., & Council On Injury, Violence, And Poison Prevention. (2021). Prevention of drowning. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2021052227.

Drowning Data. (2021). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved April 28, 20222, from https://www.cdc.gov/drowning/data

Facts & Stats About Drowning. (2018). Stop Drowning Now. Retrieved April 28, 2022, from https://www.stopdrowningnow.org/drowning-statistics/.

Varveri, D., Karatzaferi, C., Pollatou, E., & Sakkas, G. K. (2016). Aquaticity: A discussion of the term and of how it applies to humans. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 20(2), 219–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.001

Jo An M. Zimmermann, PhD, CPRE, is an Associate Professor and Academic Specialist in Recreation Studies and HHP Curriculum Development Coordinator for the Department of Health and Human Performance at Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. Reach her at jz15@txstate.edu.

Stacey Bender, EdD, LGI, AEAI, GFI, is a Senior Lecturer for the Dept of Health & Human Performance at Texas State University. Reach her at sh1564@txstate.edu.